Your cart is currently empty.

Cart

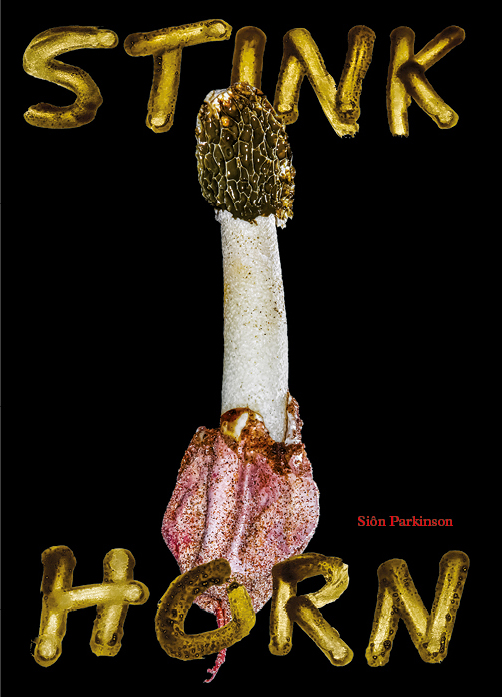

Stinkhorn

How Nature's Most Foul-Smelling Mushroom Can Change the Way We Listen

The stinkhorn mushroom is one of the weirdest wonders of the fungal world, certainly the smelliest. Ever since it was described by a Dutch doctor in a sixteenth-century pamphlet, the stinkhorn has been reported to emit odors resembling damp earth, dung, rotting cheese, decaying flesh, and even semen. It also happens to look like a phallus, bursting out of a subterranean egg to poke above the ground, where it lures insects towards its slimy, fetid cap. In Stinkhorn, artist, musician, and writer Siôn Parkinson asks: What can the pervasive stench of this mushroom and the droning noise of the flies compelled towards it reveal about how sounds and smells are combined in the imagination?

A heady mix of natural history, science writing, musicology, philosophy of the senses, and illness memoir, Parkinson uses examples of so-called bad smells to argue for a theory of Stink as a kind of “smelling sound.” Alongside images and insights from the author’s search for stinkhorn fungi in nature, the book expands upon the philosophy of listening to consider the role of the nose and the “nasal imaginary” in how we make sense of sound.

In this treatise on malodors and how they can transform the conditions for listening, Parkinson considers John Cage’s silent fungal forays, Brian Eno’s compositions with perfumes, the hum note of a vibrating bell, the “eggy” odor of space, and the author’s own hallucinated stench as the result of an epileptic seizure. What links these disparate ideas and sensory experiences can be found in a single encounter with a ripe stinkhorn mushroom.

Includes 16-page insert of a facsimile of the Neo-Latin–English translation of The Description of the Phallus by Hadrianus Junius, translated by Caroline Spearing.

Parkinson’s wonderful study follows those who have found a root system for ‘music’ in the Italian word ‘musare,’ meaning to sniff the air. Riffing off the new musicology (mycology?), he brandishes the stinkhorn mushroom to explore—in unnerving detail—what can be heard through the kind of listening that has its structural corollary in the diffusion of scent. Like the musical and olfactory notes that fascinate him, Parkinson’s work exudes ‘stank.’

— John Mowitt - author of Sounds: The Ambient Humanities

What a blast! Stinkhorn is a deliciously odorous treatise on the irresistible repellence of stink, the objectlessness of sound, and the frightening marvels of an hallucinating brain. This book is bursting with gorgeous floral notes and hilarious grim belches, reminding us of the glorious baseness that we should cease trying to rise above.

— Sally O’Reilly - writer & author of the novella Help in Cucumbers

In Stinkhorn, Parkinson forces us to reconsider our perceptual preconceptions of and preoccupations with stink. If we zoomed, tuned, and breathed in rather than averting our gaze, covering our ears, and holding our noses, perhaps we could learn to sense stink not as disgusting decay but as the energetic evidence of existence. Stinkhorn is playful, it is expansive, and above all, it emits a noisome, funky honk.

— Will Tullett - author of Smell and the Past: Noses, Archives, Narratives, and Smell in Eighteenth-Century England: A Social Sense